7th Annual Holiday Toy & Book Event Help make the holidays brighter this year!

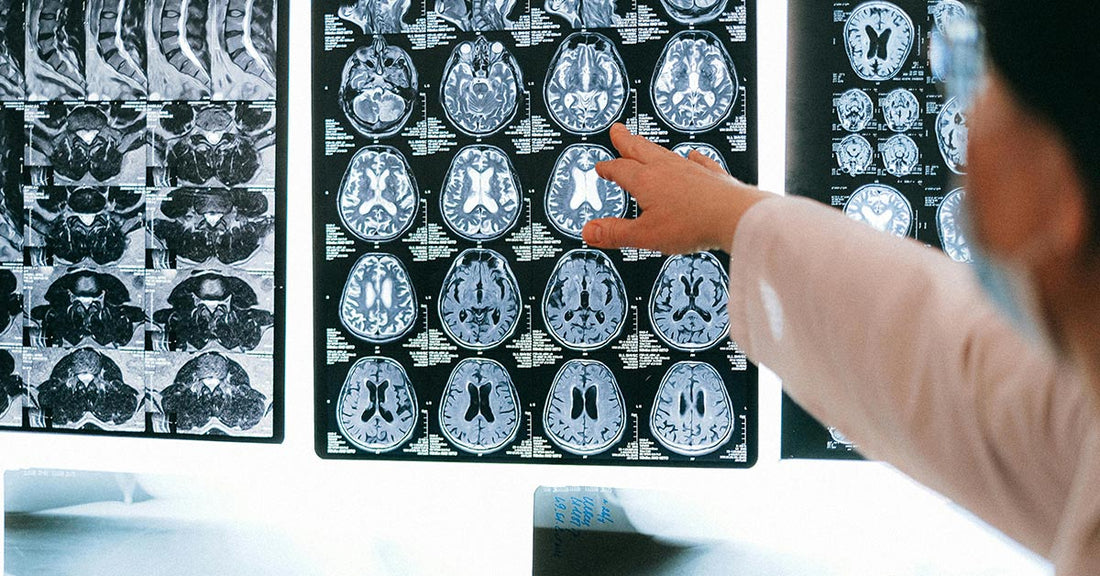

Microplastic Exposure and Alzheimer’s Risk in Genetically Vulnerable Individuals

Guest Contributor

Nearly seven million Americans are currently living with Alzheimer’s disease, a number projected to double by 2060, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While the disease remains without a cure, emerging research continues to explore environmental factors that may influence its onset or progression. A recent study from the University of Rhode Island has added a new and concerning dimension to this conversation: the potential link between microplastic exposure and increased Alzheimer’s risk in genetically predisposed individuals.

Microplastics—tiny plastic particles found in everything from food packaging to drinking water—have been under scrutiny for their potential impact on human health. In this new study, published in Environmental Research Communications, researchers investigated how these particles might interact with the brain, particularly in the presence of the APOE4 gene, which is the most significant known genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. The findings suggest that microplastics could exacerbate cognitive decline in those already vulnerable due to their genetic makeup.

The study involved 64 mice, evenly split by sex, and genetically engineered to carry either the APOE3 or APOE4 gene. APOE3 is considered a neutral variant in terms of Alzheimer’s risk, while APOE4 is strongly linked to a higher likelihood of developing the disease. The mice were exposed to water laced with high concentrations of nano- and microplastics, simulating the cumulative exposure a human might experience over a lifetime. The team then conducted behavioral tests and tissue analysis to assess changes in memory, cognition, and the presence of plastic particles in the brain.

One of the most striking outcomes was the detection of plastic particles lodged in the brain tissue of the exposed mice. This supports earlier research suggesting that microplastics can cross the blood-brain barrier, a protective shield that typically prevents harmful substances from entering the brain. The behavioral effects were also noteworthy. Male mice with the APOE4 gene displayed unusual patterns in open-field tests, spending more time in the center of the arena and resting more than expected—both deviations from normal exploratory behavior. Female APOE4 mice, on the other hand, showed diminished interest in new objects, a potential sign of impaired recognition memory. Mice with the APOE3 gene did not exhibit these changes, highlighting the possible interaction between microplastic exposure and genetic susceptibility.

Jaime Ross, a professor of neuroscience at the University of Rhode Island and one of the study’s authors, expressed her surprise at the results. “I just can't believe that you are exposed to these particles and something like this can happen,” she told the Washington Post. While the presence of the APOE4 gene does not guarantee the development of Alzheimer's, Ross emphasized that it is the most significant risk factor currently known. The study raises important questions about how environmental elements like microplastics might influence disease development in genetically at-risk populations.

It’s important to recognize the study’s limitations. The plastics used were lab-made and may not perfectly replicate the types encountered in daily life. Additionally, the exposure levels were intentionally high to simulate long-term accumulation, which may not reflect typical human exposure. Still, the research contributes to a growing body of evidence suggesting that microplastics are not just an environmental issue but a potential public health concern.

Other recent studies have added to this concern. Earlier this year, research indicated that microplastics might make the blood-brain barrier more permeable, potentially allowing toxins to enter the brain more easily. Another study suggested that these particles could cause liver damage. While none of these studies offer definitive conclusions, together they paint a troubling picture of the pervasive impact of microplastic consumption.

For individuals concerned about Alzheimer’s and overall brain health, the findings offer a compelling reason to consider lifestyle adjustments. While it's impossible to eliminate microplastic exposure entirely, there are practical steps that can help reduce it. Replacing non-stick cookware, avoiding plastic cutting boards, and choosing alternatives to synthetic sponges are small changes that can make a difference. Nutrition also plays a role; scientists suggest that a diet rich in fruits and vegetables may help counteract some of the negative effects of microplastics in the body.

I found this detail striking: the idea that microscopic particles, invisible to the naked eye, could potentially influence something as complex and devastating as Alzheimer’s disease. It underscores how interconnected our environment and health truly are. The study serves as both a caution and a call to action, urging more research and greater awareness of the substances we encounter daily.

As Alzheimer’s continues to affect millions of families, understanding all possible risk factors—including environmental ones—is essential. While genetics play a significant role, studies like this one remind us that our surroundings and choices may also contribute in meaningful ways. Continued research will be critical in unraveling these complex interactions and guiding public health strategies in the years to come.